Dr Shannon Chan's Story

Children and the Landmines

Dr. Shannon Chan’s first mission was to South Sudan in 2016 and in late 2019, she set off on her second mission to Mocha in Yemen, where she worked as a trauma surgeon and trainer to national staff.

It has become extremely difficult to obtain access to medical care in the area. The Mocha Hospital mainly admits patients suffering from major traumas, acute surgical, gynaecological and obstetrics emergencies. During her mission, an incident that really affected her was a group of innocent children killed and injured by landmines.

For people in Mocha, an area for people displaced by conflict in Yemen, simply walking on the streets puts their lives at risk. When playing on the street, a child along with a group of eight others — ranging from age 9 to 13 — accidentally stepped on a landmine and led to the explosions of a total of three landmines. Before the children could run, the landmines exploded. These landmine explosions usually cause massive injuries, not only to the child who stepped on the landmine, but also others in close proximity. The blast caused traumatic amputation of both legs of the child who stepped on it. It also causes a major thrust throwing off other children causing head injuries, fractures and burn injuries. It also caused penetrating shrapnel injuries to some.

Shannon described as five of the children in more critical conditions were first sent to the Mocha field hospital:

“As there were insufficient resources for medical care of everyone at once, nurses triaged the patients to categorise who was in most urgent need of medical care. Two of the children categorised with a red tag suffered from injuries so severe that they were beyond help. One of them had an open fracture of the skull and was already gasping for breath. The other had no obvious external injuries but was unconscious with dilated non-reactive pupils and a dropping blood pressure and heart rate. This signifies severe brain injury, likely from bleeding.

I examined the injuries of the third child, a boy, who had a red tag – a label used for those critically ill.

The fragments of landmine caused penetrating injuries tohis legs, arms and abdomen. His face was so pale that you could tell he had lost a huge amount of blood. We had to rush him to surgery.

My translator helped me call over the child’s mother to seek her permission for the surgery. As I was explaining to her the situation of that child, she interrupted me with a shaking voice, “How about the other two children?” It was only at that moment that I realised the three children all belonged to her. It was absolutely heart-wrenching to tell her that two other children, two sons, were very unlikely to survive due to the severity of their head injuries.

The mother grabbed me closer to her son’s bodies, one by one, and begged me to save them. She almost knelt to the ground. All I could do was keep apologizing that there was not much we can do to save them. It was the most difficult moments, for I knew there were no words that would possibly comfort the mother. Looking into her eyes, I can feel her desperation and hopelessness. I took a deep breath and held back my tears. I knew at that moment, the best thing I could do for her was to save her third child. The translator convinced her to let me continue to work in saving her third son’s life. During the surgery, I took out the fragments of landmines, which were like bullets, from his body and treated the internal bleeding. The shrapnel caused perforations to the kidney, duodenum, stomach and spleen. Fortunately, after the operations, he recovered well. The other six children who stood farther from the explosion suffered fractures of extremities but are relatively minor injuries and would heal with surgeries and physiotherapy rehabilitation.

Since then, the mother came to the hospital every day and took care of the third son. She would always come up to me to say how thankful she was to us for saving her third son. Despite this, and you could still see the sorrow in her eyes for the loss of her other two beloved children. I guess living in these conflict zones, one is forced to toughen up and struggle to live on. What other choices do you have if not?”

These landmines which were planted during the conflict have become hazards for the naive and innocent children. The children who survived have adapted to life since the blast—but no child should have to face these struggles. After treating so many civilians who have suffered the tragic consequences of conflict, Shannon says:

“I still feel the indescribable pain for the loss of every life during the surgeries.”

At times during the mission, Shannon felt helpless seeing the numerous injuries every day due to the conflict. what she can do as a surgeon in the midst of all the challenges is to save as many lives as possible, and to let the people know that at least someone cares.

Dr Ryan Ko's Story

A Hong Kong surgeon’s blog about field capacity building on war trauma surgery

Dr Ryan Ko, a Hong Kong surgeon with Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF), has worked in 15 missions in nine countries. Being exposed in various settings and challenges, there is one common issue that communities faced in these areas – big unmet surgical medical needs due to the impact of conflict and war.

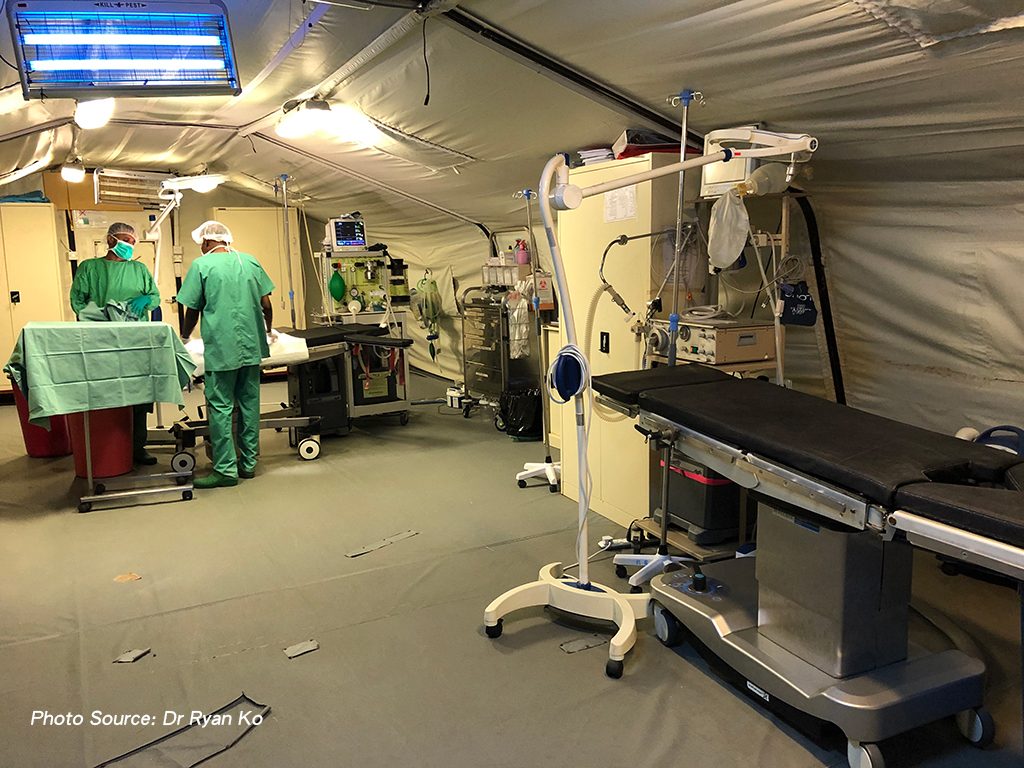

He worked in Mocha, Yemen from November 2020 to February 2021 to improve the surgical capacity of the team in the newly opened MSF emergency surgical centre.

Mocha is an ancient port city on the Red Sea. It’s near the conflict front line, so around 80% of our surgery cases are trauma related, such as gunshot and road accident wounds. Due to limited health care services, the MSF emergency surgical centre also takes patients who require life-saving care, such as mothers with childbirth complications and patients with acute abdominal problems.

In the MSF hospital, I worked with four Yemeni surgeons and nine medical doctors. With the heavy load of trauma patients admitted, my colleagues gained experience and improved their trauma surgery skills while I was coaching them.

My role was mainly to assess our staff’s skills and to give advice whenever there might be a better or alternative surgical skill. This involved many surgical subspecialities, including trauma, abdominal, thoracic, orthopaedic, vascular, urological, obstetric and gynaecological surgeries. You might be surprised that we need to cover so many areas of surgery in the settings where MSF works.

Medical skills and expertise available vary from one region to another. In some countries in sub-Saharan Africa, there are just not enough trained medical people compared to the immense needs of communities. Whereas in Middle Eastern countries, there are a good number of quality staff we can find to work with us.

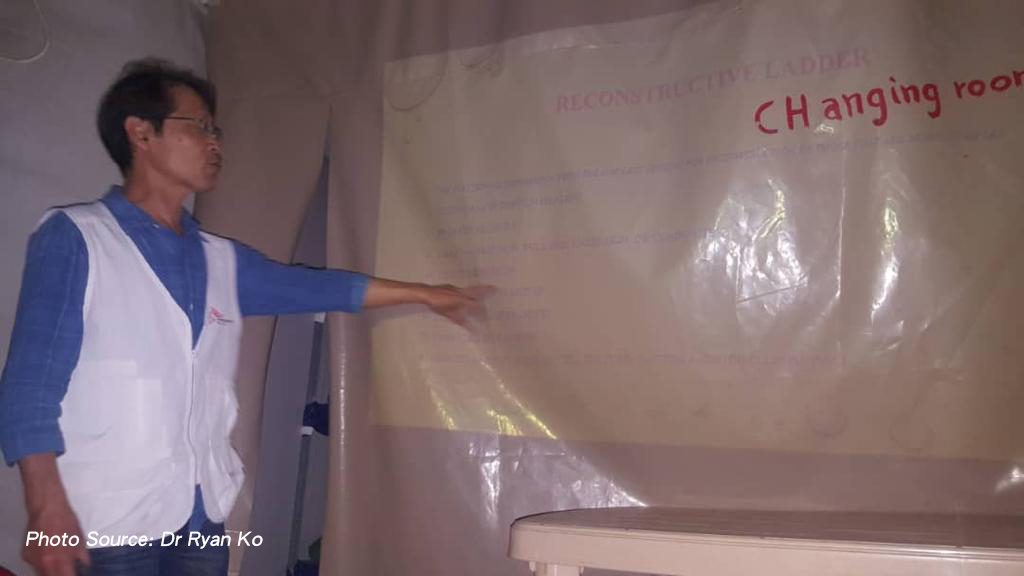

However, chronic and long-term war and conflict limit the development and acquisition of new skills which are essential for medics. The availability and access to medical training is seriously lacking. That’s why capacity building and sharing of our knowledge and experience with our colleagues in the field is one of the less talked about but essential responsibilities of field workers like me being deployed to the field. I felt that surgeons from Hong Kong like me are in a position to impart our expertise, given the standard and quality of skills we have been able to acquire. We can support the aim of ensuring that our fellow medics in war zones can run the hospitals on their own with confidence.

We strive to provide a high standard of medical care. And supporting our colleagues with training, workshops and coaching to upskill them would mean that we could help more patients at a time of distress. So in the three months I stayed in Mocha, I had some very good and friendly knowledge and experience exchanges with my colleagues in every area possible, including wound reconstructive surgery.

This procedure was completely new to them so I needed to train them in a more systematic way. After the training sessions they practice flap surgeries, a technique that is typically used to repair defects left behind after traumatic injury. During my time there, the team conducted 45 flap surgeries which benefitted 42 patients with very good results – shortened hospital stays and fewer follow-ups. The wounds healed well and lots of patients avoided the amputation of limbs, which can seriously affect the mental wellbeing of patients and their loved ones. This procedure would have been especially beneficial to the hospital, given the immense number of trauma patients we saw every day. So this new skill acquired by our surgeons brings relief to patients and also prestige to them as professionals.

At the same time, we built the capacity of the team on diagnostic ultrasound dedicated to identify trauma bleeding in the abdomen and chest. In the surgery world it’s known as extended focused assessment with sonography for trauma (eFAST). In a humanitarian surgery care settings, where patients present with major injuries, this skill can improve decisions on what could be the appropriate course of action for our trauma patients. This capacity building was also extended for our medical doctors, especially for those working in the emergency department where initial assessments of our trauma patients were done.

I have also shared my perspective as a surgeon on wound management. Since the hospital handles mostly patients who need ongoing treatment of their wounds, it is essential that our teams are able to provide the best care for healing and to prevent the breakdown of skin.

It is equally important for our nurses to be provided with new knowledge. We worked closely with those in our various wards (operating theatre, outpatient, and inpatient) on nursing care for flap surgery. Apart from concepts and theories, whenever I had time I accompanied them in their daily care of these patients.

Within a short period of time, I was very happy to make a difference by imparting my experience and knowledge to our colleagues in the field. They are the staff with the constant presence to care for people and communities in the midst of war and violence.